Balancing Benevolence

The views expressed here are Sean’s own and do not necessarily reflect those of the wider Ripples team.

I feel I have to caveat this blog post with the confession that I am relatively new to the world of not-for-profits and philanthropy so I am probably not the most qualified person to philosophise about the topics I’m going to. Nevertheless, a concoction of small events have been brewing together in my mind over the last few weeks. Neither analysis in my own head nor debate with others have led me to forming a clear opinion or summary, which is really inconvenient (and probably why I’m writing about it now!)

I say that the topics have been in my mind over the last few weeks but undertones of the central theme have really been in my mind for much, much longer: For as long as I’ve wanted to direct my energies into social enterprise/philanthropy/doing good or whatever you want to call it.

The first thing that brought these themes to the forefront of my consciousness was the BAFTAS a few weeks ago. Specifically, when Joaquin Phoenix and others proceeded to deliver speeches that COULD be described as virtue signalling, self-righteous bull****. Actually, it was before that. It was preempted by Ricky Gervais’ brilliant Golden Globes monologue where he lambasted the attendees: “You’re in no position to lecture the public about anything. You know nothing about the real world. Most of you spent less time in school than Greta Thunberg. So, if you win, come up, accept your little award, thank your agent and your God and f*** off!” See it here:

A few weeks later at the BAFTAS, Joaquin Phoenix delivered a speech in this exact vein after winning Best Actor. The next morning I saw Gervais post this on socials:

Very proud of all these actors calling out the lack of diversity at award shows. I bet if they’d have known the nominations in advance they wouldn’t have even turned up in the hope of winning themselves.

— Ricky Gervais (@rickygervais) February 3, 2020

At first, I thought ‘YES. Ricky Gervais, spot on as always. I’m sick of these celebs lecturing the world from their very luxurious pedestals, demonstrating how wonderfully “woke” they are in the most public way possible. Ricky’s right. The virtue signalling celebrities could all boycott these award ceremonies which would make a much bigger statement!’

I consider myself very rational and unbiased. I weigh up arguments. Analyse objectively. I must admit though, the reaction above was my instinctive opinion – though it wasn’t an especially strong one.

The next event happened a week or so later. I was doing our weekly shop in Lidl on Well Street. Normally I do it with my girlfriend, Aoife, but this week I happened to be on my own. Aoife will tell you, I have a sweet tooth. When we’re shopping together she has to stop me from buying a LOT of nice shiz. Like a child. I typically try to get 3 or 4 treats but it usually gets culled back to 2 when Aoife’s there.

Anyway, I’m almost finished my solo shop and I’ve got a respectable three treat items in the trolley: chocolate mini rolls, scones and a variety pack of biscuits (all Lidl-own brand of course – I’m not made of money!) I turn to head towards the tils and a woman approaches me and quietly asks “Can you buy me something?” No sad (and potentially false) backstory was attached to the question as is common with this kind of request. The woman was dressed fine and didn’t appear to be homeless. Her request was really vague, so I offered to buy her “a sandwich or something”, to which she asked if she could get some more things. This developed into a very strange and awkward conversation with her offering very vague questions and statements. It probably didn’t help that I was quite taken aback by the whole thing. I said to her to pick up £5 worth of things and I would pay for them. I then headed for the (very long) queue where I agreed to meet her.

Once on my own, my mind raced through the various possibilities of what was going on. This woman did not seem homeless. Was I being conned? Did she suffer from an addiction? Was she just in a difficult spot? I’ve always worked on the assumption that if someone is asking for food and not money, you can be quite confident they’re genuine and not a “plastic tramp” or addict or whatever. As I stood queueing I then noticed she was on the phone, whilst looking at the crisps. Down the phone she asked “So is it the normal ones you want then?” whilst holding a red tube of ready salted Pringles. This only stimulated my internal conversation further. ‘She can’t be in that much difficulty if she’s buying pringles?!’ etc etc.

The queue was very long and she was taking ages to work out what to spend the £5 on, so I continued to ponder this peculiar situation. I couldn’t help but feel really guilty, as I looked down at the contents of my trolley. The chocolate mini rolls. The scones. The biscuits. The mid-range fish cakes (not quite premium, but not the unthinkable “white fish portion”-type either.

I don’t need so much of this stuff, but I buy it all the time. Some people can’t put dinner on the table, some don’t have anywhere to stay. With the money I spend on sweet treats (not to mention alcohol, that’s a whole other blog post), I could literally solve these basic needs for 2-3 people. But I don’t. I eat the treats. I go to the pub.

She eventually appeared just as I was being served and put her basket down (to the awkward confusion of the checkout girl and other shoppers, which I attempted to downplay). She had chosen a sandwich, a few sweet pastries and a big bottle of Pepsi – the Pringles didn’t make the cut after all. I returned to my judgements about the severity of her situation based on the items she chose to spend this so generously gifted £5.00 “budget” on. A budget which was less than the price of a f-ing pint in London. These judgements were very swiftly put to bed as I realised it was not my place, given I knew nothing about her situation or what happiness or respite these “treats” would bring to whoever they were for.

My mind then wondered to the potential recipients of these treats. Were they her children? Can you even begin to imagine what that situation must feel like? Having to ask strangers to help you so you can provide such simple treats for your children? Even though you could argue that I did my “good deed for the day”, the good deed only left me feeling guilty. Guilt about my privilege. I’ve felt this before. I tend to feel it whenever I do a “good deed” or volunteer. I think it’s because these situations shine such a strong light on the “haves and have nots”. It’s a negative experience.

Fast forward a few days later. It’s the morning after the Oscars and videos are circulating on Facebook as they do. Joaquin Phoenix was there again, preaching away. This time, however, I could not help but agree with and be moved by the content and delivery of his speech:

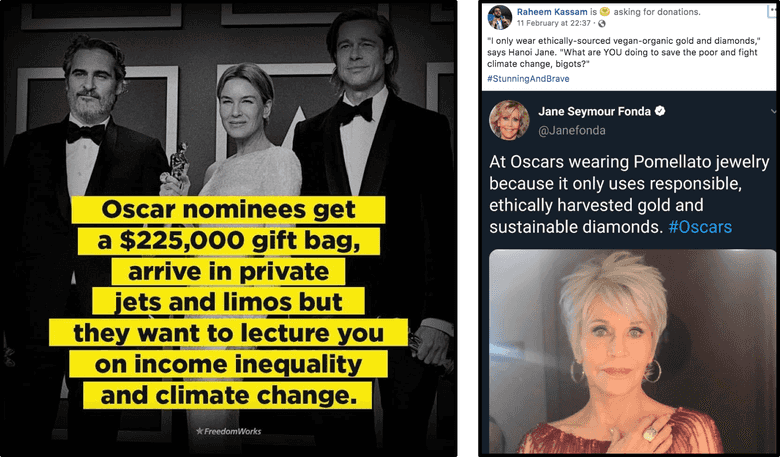

I returned to reconsider my instinctive opinion of these "virtue signalling, preaching, do-gooder celebs" and tried to process my feelings towards them. On one hand, I broadly agree with the content of their speeches. On the other, I feel frustrated and patronsied. These are the feelings that lead to this kind of reaction from the internet.

My thought process became: ‘If I agree with the message it becomes a question of whether these speeches actually affect positive change.’’ What’s the “net good” of the speech? If they don’t have any actual impact then theyarejust pointless virtue-signalling, self-indulgent and self-righteousperformances. I don’t think they do affect positive change*directly.*For example, a non-vegan is not going to turn vegan after listening to Joaquin Phoenix’s lecture about it. If anything, it might push them further away from veganism in rebellion. However, I suspect it does galvanise people who already think alike and they, in turn, probably ramp up their influence and persuasion to their relatives. So, indirectly, perhaps these speeches do have an impact. *Disclaimer: I’m not vegan. I don’t think the topic of the lecture is important to this debate, it just so happened that veganism was one of many messages Joaquin Phoenix was peddling*.

The other aspect of the whole debate is practising what you preach. Does Joaquin Phoenix preach about sustainability but then get private jets around? We just don’t know. So it’s not fair to assume that he does. BUT EVEN IF HE DOES, can we blame him? Can he not hold the views he does about sustainability, even lecture others on them, if he is doing his part in other ways? Perhaps a necessity of being a hollywood star actor is getting the odd private jet. If acting is his passion, can he not be allowed this vice, especially if his sum total social impact (“net good”) is positive?

To paraphrase someone in my immediate family: “The problem with Joaquin Phoenix is that it’s easy for him to stand up there with all of the money in the world and tell everyone how to be a good person. Ordinary people have more pressing concerns, like making ends meet!” There’s two problems with this:

- You simply do not know what PERCENTAGE of his resource Joaquin Phoenix devotes to the issues he’s speaking about.

- If YOU had the same money and resources as Joaquin Phoenix, you simply do not know what percentage of your resources that YOU would donate.

With these two points in mind, can you reasonably judge Joaquin Phoenix and others for using their position to get these messages out? I would argue not. If you knew all of the facts, then you could make a reasoned judgement. You could assess whether they’re hypocrites or not.

This is where my random Lidl story becomes relevant (I hope). I’m fairly passionate about solving homelessness. I feel incredibly guilty when I see homeless people. I have volunteered at homeless shelters the last couple of winters. That doesn’t mean I put all of my resources (time or financial) into solving it. I donate a very small portion of my resources to helping (less than 4%). I still have a million selfish interests and guilty pleasures that take precedence over my interest in supporting homelessness. As you’ve read, I spend money on chocolate mini rolls, variety packs of biscuits, scones, beers. I spend my time playing football, socialising, watching Netflix. I could sacrifice all of those things and allocate those resources into helping homelessness. But I don’t.

The following analogy requires a big jump between worlds, but bear with me… Say my guilty pleasure is chocolate mini rolls and beers but I still donate 4% of my resources to supporting homeless charities. You probably wouldn’t think of me as a bad person or a hypocrite. By contrast, if Joaquin Phoenix’s guilty pleasure is a passion for acting which requires the occasional private jet, but he offsets that by donating 30% of his vast fortune to sustainability charities so that he is beyond carbon neutral, people will still think him to be a hypocrite. If this hypothetical comparison were somehow quantifiable and standardised, I would guess that Joaquin’s relative “net good” (as a PERCENTAGE of his resources) is much greater than mine. So, before making snide comments about these celebs, perhaps we should think about our own RELATIVE “net good” first… I appreciate that trying to distil and standardise this complex issue into some “relative net good” metric is pretty unhelpful because you’re comparing apples with pears – but it’s the best I can come up with.

We all like to think that if we were gazillionaires we would do loads of good. And I’m positive that 99% of the population would. But let me ask you two questions:

- Would you agree that if you had £2,000,000 in your bank account you could live a very, very comfortable life?

- If you had £100,000,000 in your bank account, how much of it would you give to charitable causes? If your answer to question 1 was YES, then you should be giving a tidy £98m to charity if you claim to be virtuous.

The trouble is, you don’t have £100m in the bank and so you don’t truly know how much you’d give away. Personally, I know I would give away at least 50% of my hypothetical fortune. I like to think I would give away somewhere between 80-90%, but I can’t be sure.(Side note: I’m struggling with this specific conundrum right now as I look to join Founders Pledge – where you pledge a percentage of your potential earnings from company share sales to a charity. E.g. if I sell my shares in Ripples for £5 million years from now, I will be legally obliged to donate X% of my earnings to charity. Check them out, it’s great.)

Whilst debating this whole situation in my head and with my Mum this afternoon, I came to the very muddy summation that it really comes down to the unquantifiable inner-conflict that everyone has between trying to be a good person (benevolence) and human desires (self-interest). Although I am a staunch atheist now, I was raised a Catholic and some of the agreeable messages that stayed with me are:

- If you’re giving to charity, give quietly (and for the right reasons)

- To be a truly good Catholic (or from my perspective, just a truly good human being with absolute integrity), you should relinquish all “earthly” possessions and basically make it your life’s mission to help others (and serve God, if you’re religious).

In my heart I fully agree with both of these lessons. But the second one is just not realistic (unless you are a monk or something similarly extreme). We are human beings and instinctively strive for nice things. It’s about balance. And the balance between helping others and having nice stuff isn’t a simple one. The balance required for one person to sleep at night may be very different to the next person.

For example, I know that I will never be the type of person to have loads of expensive material items that I never use. If I’m ever rich, I won’t have a Porsche that sits in the garage for months on end. I’d feel too guilty. I would have a very nice house though and go on amazing holidays.

Then there are some amazing people and volunteers out there who devote SO MUCH of their resource to other people. They probably couldn’t live with themselves wasting money on beers and chocolate mini rolls like me. They live incredibly simply. It’s so amicable.

It’s all relative and everyone’s different.

We’re shaped by previous experiences but mostly, I think, by what’s immediately visible to us. If we’re thrust into an emotionally stressful and uncomfortable situation (such as visiting a poverty stricken village), we are compelled to forego self-interest and act very generously. But then we go back to our warm homes and the urgency fades back into our periphery pretty swiftly. It’s really easy and natural to turn a blind eye/stay proactively ignorant, because the injustices around the world are really difficult and uncomfortable to think about, especially if we do not feel empowered to help solve such major issues.

The balance is further complicated by our beliefs about “net good”. For example, one might believe that leading a traditional life and doing a traditional job is their own best way to contribute to society (as opposed to giving their possessions away and becoming a monk!) For me, I believe that investing my resources into making joinripples.org a success is my best way of doing good for society. However, this moral motivation is made impure by undeniably selfish human desires – my ego is desperate for it to be a success. It would feel SO good to be part of the founding team of a company that raises millions for charities. The two motivations are inextricably linked.

I think it’s important to accept that this “conflict” is normal. Our psyche is not black and white. We are complicated and having several motivations that are seemingly at odds with one-another is natural and reflected in our physical actions all the time.

Joaquin Phoenix is not completely pure and doesn’t claim to me. Same goes for me, and for you. Only the the monks are truly pure! Apart from this one from The Hangover 2.

If you’re reading this, I’d love to hear your thoughts.

Note: This blog post was not a paid ad for Lidl’s Rowan Hill Chocolate Mini Rolls, as good as they are.